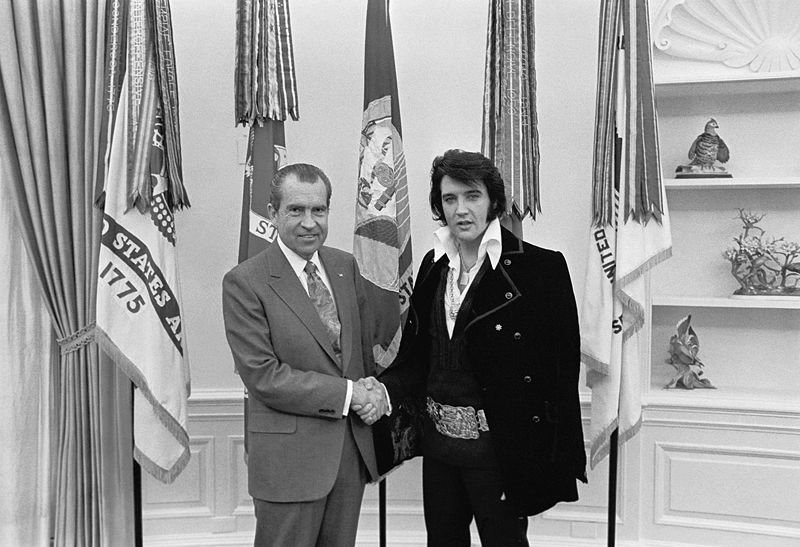

In January 2011, David D. Robbins Jr., author of the blog The Fade-Out, and Fernando Ortiz Jr., author of this blog, Stillness of Heart, shared their thoughts about three presidential quasi-biopics by film director Oliver Stone: “J.F.K.,” “Nixon,” and W.” They discussed the films and the politics surrounding them. They also considered what the films show us about ourselves and about American politics in general. This is a recently re-edited version of that conversation and is republished — with special permission — on Stillness of Heart. Its ideas and issues still resonate throughout our current conversations about film, history, politics, and culture.

*****

(Letter No. 1): From David D. Robbins Jr. to Fernando Ortiz Jr.:

“Karl, in Texas we call that walkin’.”

Hey Fernando, let me first say, I’m so glad to be talking about these films with you. I can think of no better and more knowledgeable partner. Taken in totality, these are such crucial films to the American movie canon. It seems we’re forever minted by them. I want to start off talking with you about the lesser of the three films, “W.” Much like you, I’ve seen each of these films more times than I can count. I re-watched “W.” a couple of days ago to see if I felt any different than I did the first time I watched it. I saw it at the theater when it came out, and enjoyed it — but it felt trite — something I never felt while watching “J.F.K.” and “Nixon.” I thought I remembered reading somewhere that director Oliver Stone said he purposefully made it trite, because then-President George W. Bush wasn’t really worth a serious look.

The first thing that struck me about this film was just how closely it stayed to the script. The near-death pretzel episode. Bush getting his cabinet lost at Crawford. They were all stories we’re familiar with, and the film’s scenes felt a bit like parody or vignettes stitched together. When I saw the film at the theater, it received a ton of laughs, especially during scenes where Bush Jr. mispronounced words, or got tangled in common phrases. I chuckled a bit, but didn’t find it all that funny because here was a man whose decisions resulted in the deaths of more than 4,000 U.S. servicemen and more than 10,000 Iraqi civilians. Much like what he did in “Nixon,” Stone made Bush sympathetic in “W.” (Unlike what conservative critics, who probably never even watched the film, characterized Stone’s portrayal to be.) And that rubbed me the wrong way.

Stone put some very delicious lines in Bush’s mouth, like that scene where he and political strategist Karl Rove are discussing him taking a run at the presidency. Rove lists a few things Bush needs to change about himself to get votes on a national level. He asks Bush Jr. about his cocky swagger. Bush replies, “Karl, in Texas we call that walkin’.” It’s a fantastic line. Or when Bush, in the Situation Room, says, “I’m not Bill Clinton. I’m not gonna use a $2 million missile to destroy a $10 tent and hit a donkey in the ass.” Granted, I have to give some respect to Stone for not making Bush Jr. into a completely one-dimensional character just to fit a popular conception. But it must have been tempting. There are stories told by many historians that are even more ridiculous than the ones presented by Stone. Bob Woodward tells a story in “Plan of Attack” about Bush Jr. the first day he was briefed by the Joint Chiefs. Vice President Dick Cheney was falling asleep. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumseld kept asking the group to “speak up” because he was so hard of hearing. Apparently, they were describing the two no-fly zones over Iraq, with a map on the table. To outline the areas on the map, they used three mints. Bush Jr. grabbed a mint and ate it. A few minutes later he asked if anyone wanted the second mint. By the end of the meeting, he eyed the third mint and a JCS staffer, spotting his gaze, quickly grabbed up the mint and handed it to Bush — who popped it in his mouth. It doesn’t get any funnier (or sadder) than that.

At first I didn’t like Thandie Newton’s Condoleezza Rice accent. It threw me off. But I suppose it didn’t much matter — because much like her role as Bush Jr.’s National Security Advisor — she remained relatively mute during the movie too. I don’t think there’s ever been a head of the NSA so befuddled by the job — so much so, she simply was a Bush Jr. lapdog. Fernando, imagine Brent Scowcroft or McGeorge Bundy acquiescing to the president’s whims without much interjection or give and take.

Let it be said, I’ve never been a fan of Bush Jr., but I don’t hate the man either. Being president is the most difficult, thankless, life-sapping job on the planet. Tough decisions are made everyday that would crush a normal person. But I do dislike Cheney and Rumsfeld. Thousands have lost their lives and limbs for the egos of those two men. Note how often Stone frames Cheney just at the edge of the picture, or barely within the periphery, lurking in the darkness. Right at all the crucial moments, he jumps in with his point of view. It’s accurate from all the books I’ve read of the man, including the brilliant “Angler” written by Washington Post writer Barton Gellman. Cheney isn’t a complicated person to understand. He’s been in politics for 42 years, and according to Woodward’s “Plan of Attack,” he even held a meeting about “schooling” the new president on Iraq with departing Secretary of Defense William Cohen before Bush Jr.’s inauguration. In other words, Cheney had his eye on Iraq, Saddam Hussein and Iran before he was even officially vice president. He was such a runaway train that even his colleagues said he was “obsessive” about Iraq. We only need to read Jane Mayer’s “The Dark Side” to get an even larger picture of his paranoia. Add this to the calculated opportunism of Rumsfeld (who clearly suffers from the ‘Smartest Man in the Room’ syndrome), a dysfunctional intelligence apparatus headed by a clueless Rice, the tragedy of 9/11, and Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz’s memo, and you’ve got a perfect storm.

History is messy, and often it’s a meeting of perfect storms. We don’t make history as much as history sweeps us up. What happens if JFK doesn’t go to Dallas? What if the often-brilliant Nixon stopped thinking it was his administration against the world? What if Bush Jr. didn’t have Cheney whispering into his ear like some evil Lady MacBeth? What if 9/11 never occurred to push Bush Jr. away from Secretary of State Colin Powell’s thinking and into the realm of war-machine stalwarts like Cheney, Rumsfeld and Wolfowitz? Just today, I opened up my newspaper to read Cheney daring to talk about current president Barack Obama’s character and his chances for a second term. If I was Obama, it would be hard to swallow lectures from an unapologetic liar, who from day one camped out at Langley trying to force the intelligence to fit his script — turning 9/11 into a phony search for WMDs he knew didn’t exist, and later inventing a connection between al-Qaeda and Saddam in order to push his vision. Cheney is still at it. Still desperately trying to re-write history. Rumsfeld, who had been in politics even longer than Cheney, has quietly and thankfully fallen away into silence. It’s funny how in the movie, whenever ‘Rummy’ speaks, Bush Jr. just rolls his eyes and goes on to the next person. Rumsfeld’s complicated verbiage, or “known unknowns,” impressed Bush about as much as it did the press corps — which is to say not at all. He was shown in the film and in books like “By His Own Rules” (by Bradley Graham) to be a guy who liked to keep insulated. No one would get to know the real Rumsfeld, if that person even exists. He’d give points of view, but rarely let those around him know exactly why he gave them. Ultimately, this administration’s decision to go into Iraq was disastrous in battling terrorism. It refueled a jihadist mentality in Muslims around the world and made Osama bin Laden’s prediction that the U.S.’s long-range goal really was occupation, control of the region and command over oil wells seem all the more correct.

I’m sorry I’ve veered so far away from the movie. But I felt like starting off the conversation with a seriousness the movie lacked. The scenes with Bush Jr. dreaming of baseball came off like a tedious metaphor. Bush Jr.’s ‘come-to-Jesus’ moment was treated fairly by Stone, but it too felt stale and obligatory. Perhaps the one question answered by this movie was how in the world a beer-guzzling, doltish, young Bush could land the bookish Laura Welch. The film presents Bush as a bumbling charmer at a barbecue, where he meets his future wife. Talking with his mouth full, spittle flying, he proceeds to sweep her off her feet. The movie never touches the topic of Welch killing a friend in a car accident, which is fine because it’s not a movie about her. But I suspect that had a major effect on the type of person she became. An accident like that makes one very slow to judge the faults of others. I could see her being very forgiving about Bush Jr.’s defects. It’s a life perspective that transformed her into one of America’s most beloved first ladies. I enjoyed this film. But for me it doesn’t come close to what Stone did in “Nixon” or “JFK”.

(Letter No. 2): From Fernando Ortiz Jr. to David D. Robbins Jr.:

“You’re a Bush! Act like one!”

David, it’s a dream come true to have this virtual conversation with you. Over the last decade, so many of Oliver Stone’s films have made it into our best conversations and casual analyses of the insane world around us. It only seems right to take a moment to focus directly on some of Stone’s best work.

Beginning this series with “W.” is quite timely. Recent days saw Tony Blair’s second appearance before the Chilcot committee, which is investigating British involvement in the 2003 Iraq war. Deadly bombings shattered the notion of a tense peace returning to Baghdad. And at a symposium in College Station, Texas, George H.W. Bush led the architects of the 1991 Persian Gulf War in a re-examination of their strategic decisions, including the decision not to topple Saddam Hussein’s government after Allied forces ejected the Iraqis from Kuwait.

I mention the 1991 war because I sometimes consider the 1991 and 2003 Iraq conflicts as two pieces of a larger whole, a larger era bookmarked by the two Bush presidencies, with the latter war a grand symptom of the bitter relationship the disappointed father shared with his defiant son. As a budding novelist, that relationship has fascinated me for so many years, and Stone’s illustration of that relationship is what, for me, elevates “W.” from the otherwise broad and shallow strokes brushed across a rather cheap canvas. For nuanced explorations of the fascinating power plays throughout the second Bush administration, the intellectual and psuedo-intellectual fires fueling the drive toward a second Iraq war and the catastrophic consequences of so many astoundingly shortsighted decisions, one needs to look no further than the brilliant PBS series “Frontline.”

To me, aside from the exploration of the fragmented father-son connection, the value of “W.” lies in how it challenges us, like all decent biopics, to sympathize with George W. Bush as a person. I agree with you that Stone succeeded at that. We see W. daydreaming during meetings, make terrible jokes, sit on the toilet as he talks to his wife, dance on bars, yearn for parental approval, demand respect, and dream of a happy future. Who among us can’t feel the same tinge of regret, loneliness or hope as we wander through our mediocre days, seemingly locked into our orbits around the men and women who dominate our emotional lives? Like some of the smartest reporting on W., the film warns us to never make the mistake of underestimating him, as so many of his opponents did, and as his father did. It’s a daring approach for Stone, Josh Brolin, and many of the film’s other actors who spoke out against the Iraq war and against the men and women they portray. I wish they received more credit for that artistic decision and a bigger audience to savor it.

It’s a tribute to Stone and his team that they managed to assemble a film of such breezy intelligence and mischievousness so quickly. A small project like this could have been so easily relegated to TNT or Showtime, never to be seen again, except in the $3 DVD bin at Wal-Mart. The director was blessed with an incredible ensemble, and that also is one of the aspects that elevates this film. In the DVD commentary Stone said it was his best ensemble ever. As you know, I still insist “Nixon” had the best cast, followed by “JFK.” But we’ll save that issue for another day.

I thought Condi Rice deserved a deeper, complex portrayal, far from the one Thandie Newton gave her. I don’t even know why they wasted her time as an actress. The role was nothing. As I watched her, I kept picturing in my mind those classic Oliphant editorial cartoons of Rice as a bird, squawking and repeating everything W. said. Rice deserved better, and I hope that a future, more serious film of this era takes a closer look at her. Yes, she was ineffectual as national security adviser, and certainly she was overwhelmed and outmaneuvered by Cheney and Rumsfeld. I suppose I just want a film that will show that with patience, intelligence and layered dramatic force, even if it shows her frustration, her private insecurities, and her determination to hit back when she becomes secretary of state. Take a moment to make her human too, Oliver. I was also unmoved by Jeremy Wright as Colin Powell. I love Wright as an actor, and he did his usual fine job here, but he just didn’t project Powell in a full-bodied way. Powell too deserves a major examination on film.

I want to say the same for Rumsfeld, but Scott Glenn’s smarmy, sneering portrayal wins me over every time. It’s a little bit of his drug-dealer from “Training Day” and a little bit of his Jack Crawford from “Silence of the Lambs.” Then he’ll smile, settle back into his slime and let the audience’s memory do the rest. Naturally, thanks to the real Rummy and his mutated Churchillian acrobatics with the English language, Glenn gets one of the best lines of the movie, a classic: “Sir, the absence of evidence is not the evidence of absence.” I still laugh every time I hear that. Maybe we’ll get a better view of Rumsfeld after his sure-to-be moronic but deliciously controversial memoir, “Known and Unknown,” is published on Feb. 8.

As for Richard Dreyfuss as Cheney, I can’t think of anyone who could’ve done a better job portraying the vice president. I can only imagine what must have been going through Cheney’s mind as he watched a subservient, intellectually listless president follow his lead in shattering the spotlights of democratic accountability and moral decency, thereby creating that dark side to this war on terror. Bush didn’t just unlock the doors to the gun rack of executive war powers. He threw the keys to Cheney and told his neocon barbarians to lock up when they were done. The look Dreyfuss almost always seems to have on his face in “W.,” that particular gleam in the eye, exclaims, “I can’t believe my luck! I can’t believe this is happening! How many moments had to align in the universe for him to be president and me to be his co-president?!?!” Dreyfuss has always been brilliant at playing complete bastards. Just look at two of my favorite bastards, Bill Babowski in “Tin Men” and Alexander Haig in “The Day Reagan Was Shot.” Both films were the blackest of black comedies, perfectly attuned to some of the best moments in “W.”

My favorite performance — I won’t say it was the best performance — was James Cromwell as George H.W. Bush. “What do you think you are?” he bellows to his screw-up son, “A Kennedy? You’re a Bush! Act like one!” I loved that line. It represents the seismic faultline between father and son, fracturing that relationship I found so interesting, as I said earlier, and perhaps exposing lifelong vulnerabilities in W. that Cheney, Paul Wolfowitz and Rumsfeld exploited to drive forward their own agenda. “Don’t act like that other Bush,” they seemed to hiss like serpents from a tree branch. “Don’t deliberate. Don’t draw on the experience from a vast diplomatic career. Ignore history’s lessons. Act with your gut instinct. Act with your heart.” Stone’s W. heard them well, and he agreed with their tempting reassurances that everything was going to be OK.

George H.W. Bush could only look on helplessly as he saw the catastrophes of Iraq and Afghanistan consume his son’s presidency. The Beast, as Stone’s Nixon would have seen it, turned on its master for one final bloody meal. Cromwell’s performance, somehow both cold and loving, distant and supportive, reminded me of how much still remains to learn about H.W. Bush, how unappreciated he still is, and how amazing his career truly was, long before he was vice president to Ronald Reagan, long before Dana Carvey portrayed him as a befuddled, brainless wimp. H.W. Bush was everything Reagan pretended to be.

And therein lies the last elevating value of “W.” It drives me to learn more about W.’s father, the post-Cold War era he inaugurated, and how his Democratic and Republican successors shaped what he left behind. It drives me more to learn about his family, and about the sons who looked up to him for approval, support and guidance. And it drives me to learn more about that one son who thought that rejecting his father’s example would earn his father’s respect, even at the cost thousands of lives and the guarantee of a prominent place in the blood-stained catalog of American infamy.

(Letter No. 3): From Fernando Ortiz Jr. to David D. Robbins Jr.:

“We’re just a patsy!”

By 1991, I was aware of Oliver Stone as a film director, particularly for his films “Platoon” and “Wall Street,” but he wasn’t someone I considered a role model. I was 17, and as I looked forward to finally graduating from high school and moving on to college, I thought about what I wanted to do with my life. Perhaps join the military, like my grandfather. Perhaps study history and, like narrative historian David McCullough, write about it. Perhaps simply write, like novelist James Michener.

I briefly considered studying film, perhaps even becoming a film director someday, like Francis Coppola or Martin Scorsese. Now those were role models. Stone hadn’t yet earned a place in my pantheon. And yet he was the one who came along with a film that year that electrified all of my passions. “JFK” was like a meteor strike, driving right into the core of my imagination and intellect, changing forever my understanding of how powerful a bold, historical film could truly be.

OK, “historical” may not be an appropriate word to describe what Stone throws at you. Rolling Stone called the film “a dishonest search for the truth.” But many other reviews used the word “riveting.” Roger Ebert called it “a masterpiece.” The Washington Post said it best: “It’s not journalism. It’s not history. It is not legal evidence. Much of it is ludicrous. It’s a piece of art or entertainment.”

I couldn’t tie my own shoelaces when I was 17, but I knew enough not to take the film seriously, no matter how dazzling it was. I staggered from the theater and into humid Christmas-time Texas Gulf Coast seabreeze, and for weeks I remained dazed and tingling and inspired by such a creative imagination. I was disappointed by how many people despised the film because they took it all too seriously. It’s too bad Stone never prefaced the film with a note like, “This is not to be taken as a sincere exploration of what happened and why, but simply a playfully creative summary of all of the crazy theories out there. Do your own damn research like a normal, intelligent American and decide for yourself.”

As an aspiring filmmaker — or so I thought myself to be at that tender age — “JFK” was the master class on bold, controversial filmmaking. But it also served as the supreme cautionary example. I saw Stone irresponsibly promoting his work as a credible thesis worthy of defense, worthy of consideration among the bitter ranks of men and women committed to exposing the supposed conspiracy behind the assassination. It wasn’t enough for him to accept the laurels from critics who loved his vision, who were moved by his fearless confrontation of the “story that won’t go away,” as the film was subtitled. It wasn’t enough to create a striking, ingenious kaleidoscopic freefall through the caverns of distrust and insecurity looming under the sense of American pride. He had to take the film as seriously as his critics did.

What I loved then and still love now about “JFK” is how it plays with history, the way Picasso played with the bombing of Guernica, the way HBO played with the fall of the Roman Republic and the Ptolemaic dynasty. Everyone sees everything differently. How boring would life be if everyone saw everything the same, and in some sense the film understands that. The film’s beauty and power comes from the depth of its distortions, from the way the filmmakers mopped up all of the paranoia, ignorance and fear pouring from the wounds fired into the American identity, strained it through their own mutated agendas and beliefs, and served us this putrid, blood-red broth, daring us to drink it. History was merely the paint. Our own imaginations were the canvas, and what amazing work did those deranged painters produce.

I later savored the descendants of that pop culture on-screen paranoia in “The X-Files” and in “Millennium,” where FBI Agents Fox Mulder, Dana Scully and Frank Black battled shadowy quasi-governmental conspiracies, and in the epileptic corpse that was “24,” where no season was complete without some ridiculous presidential coup d’etat or paramilitary operation. “JFK’s” older, smarter, and more insanely brilliant sibling, “Nixon,” took it all to a whole new level — it was the greatest of Stone’s imaginings — and it still inspires me. Any high-minded musings about why Kennedy was killed came from Robert Stone and “Frontline.”

Throughout the subsequent years and decades, almost none of those descendants affected me as deeply as “JFK.” It was for Stone definitely a big step forward into a new phase of chaotic, energetic filmmaking and film editing, so different from the somber elegant styles used to illustrate the lush, deadly Vietnamese jungle, the strained loneliness in “Talk Radio” or the cold Wall Street boardrooms. Perhaps there were hints of the flashy, fever-dream experience in “Born on the Fourth of July.” Certainly “The Doors” sent the fame-drunk and drug-addled characters careening through spectacular reels of Stone’s twisted vision.

But “JFK” achieved a new level of surreal imaginings for me. I saw not simply a vision induced by drugs or tropical heat or lust for power. It was a story of murder, one of the greatest of all murders, deconstructed not just moment by moment, but sensation by sensation. How many shots were heard? What did people see? How did they feel? Layered in between comprehension of those sensations are flashes of what they think they heard, blurred images of what they think they saw, how they absorbed what had happened and what warped those absorptions. Half-shrouded faces in the dark, puffs of smoke, black streaks of malice snaking along sunny motorcade routes, rifles aimed, machetes gleaming in the humid night, breaths frozen in time, bodies wheeled away, heartstopping nightmares, hot flashes of rage, blood turned cold, screams, silence — Stone’s cameras imagined it all for us. History and myths were somehow splintered — some conspiracy fanatics would say “shattered” — and then re-assembled to resemble the mutated American monster he argues we became after Nov. 22, 1963.

Like everyone else, I can’t help but wonder what life would have been like had Kennedy not been killed. He may have dropped Johnson as running mate in the 1964 presidential election. Would Kennedy have picked someone more liberal? What would have happened to his civil rights legislation, which needed at least some southern Democrats to vote for it? Johnson at least was one of their own, who wielded his own mighty arsenal of determination and tactical brilliance when faced with a raucous legislative process. Are we so sure Kennedy would have pulled out all American forces from Vietnam? Certainly we can all think of a more recent Democrat in the White House who has not only reversed his position on pulling out of an unpopular, pointless war, but has escalated and prolonged it. How would Kennedy’s deteriorating health affected his second term? His back was always a major issue. In “Unfinished Life,” historian Robert Dallek said Kennedy wore a back brace during his ride through Dallas, holding him upright. Oswald fired three shots at Kennedy. “Were it not for the back brace, which held him erect,” Dallek writes, “a third and fatal shot to the back of the head would not have found its mark.” What about Kennedy’s reckless behavior? Bobby Kennedy worked tirelessly to quash news stories about Kennedy’s womanizing, as J. Edgar Hoover’s intelligence file on Kennedy’s extracurricular activities grew thicker every month. No matter how polite the mainstream media remained in the mid-1960’s, the shadows of some looming scandal or potential blackmail was always darkening the skies over the administration’s future.

The dreamy musings about a world caressed by two-term Kennedy presidency (we can all agree he would have defeated Barry Goldwater) always make me smile, reminding me of how perversely (and politically) lucky Lincoln was to die when he did. You don’t ever see people sitting around wondering what great things James Garfield or William McKinley would have done in the world had they not been killed. No one is accusing Chester Arthur of masterminding a government takeover. You don’t hear whispers of how Theodore Roosevelt managed a conspiracy to not only take down McKinley in Buffalo, N.Y., but also to frame Leon Czolgosz as the patsy. Even for those presidents who died of natural causes, you don’t see movies speculating about a devious John Tyler leading a coup d’etat to take down Old Tippecanoe. “Naw, man. You don’t need a coat. You’re Old Tipp! You can handle two hours in the cold and rain! Take your time reading that inaugural address.”

I suppose it comes down to public image, something Kennedy always had in his favor, especially in an age without HD television or a media that would have breathlessly told us about the rivers of steroids, painkillers and other drugs swimming through his bloodstream, his back braces, crutches, past surgeries and other health problems. Added to the tragedy is what he left behind: a young, unhappy wife and two small children oblivious to their parents’ emotional distance. Americans love youth and vigor, even if it’s manufactured, and especially when it’s lost. When it comes to McKinley’s assassination, historians seem to be more excited about the rise of young Theodore Roosevelt, the perfect man for the new century, a young leader for a young country, blah, blah, blah. Rest assured, if it had been President Johnson murdered and Vice President Kennedy who stepped in to take over, we would have heard the exact same sentiments. “Lyndon Who? Oh, yeah, the guy who finally got out of JFK’s way.”

Over the years, Stone’s hopefulness planted in me the seeds of cynicism as I studied more of American history, learned the cycles of how power is distributed in an American democracy, and bitterly accepted the limits of what can actually be accomplished within the system of checks and balances. But sometimes I will set all of that aside, relax and remember not to take it all so seriously, certainly not as seriously as Stone does. So I’ll reach into my DVD library and pull out “JFK” for yet another viewing. It still remains one of my all-time favorite films, where, ironically, I can set aside all of that grumpiness and sadness, reach for some popcorn, and savor yet again my favorite line: “Kings are killed, Mr. Garrison. Politics is power. Nothing more.”

Indeed.

![IMG_1346[1]](https://stillnessofheart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/img_13461.jpg?w=840)

You must be logged in to post a comment.